6 October 2020

What pay gap?

Fifty years on from the Equal Pay Act, women on average are still paid much less than men. Some claim that the difference between men and women's average earnings is not a problem, while others call it incontrovertible proof of gender discrimination in the labour market. Unsurprisingly, neither group is entirely right. This blog post aims to answer three principal questions, with a focus on UK data:

- What is the gender pay gap?

- Why care about the pay gap?

- What causes the pay gap?

What is the gender pay gap?

"The gender pay gap is calculated as the difference between average hourly earnings (excluding overtime) of men and women as a proportion of average hourly earnings (excluding overtime) of men’s earnings. It is a measure across all jobs in the UK, not of the difference in pay between men and women for doing the same job."(ONS)

In 2019, the UK Gender Pay Gap amongst all employees was 17.3%.

It is the 4th largest gap in Europe, and above the average of 13% for OECD (mostly rich) countries.

How has it evolved over time?

Since the 1990s, the wage gap has fallen from around 30% to the current 17%. This is partly explained by women’s education levels catching up with, and then surpassing, those of men. In fact, women now earn less on average, even though they are better educated on average.

The gender wage gap has decreased significantly for those with less education, from 28 to 18% for those with education up to GCSE. But it has not fallen at all in the last 25 years for the best-educated: female graduates still earn 22% less than male graduates.

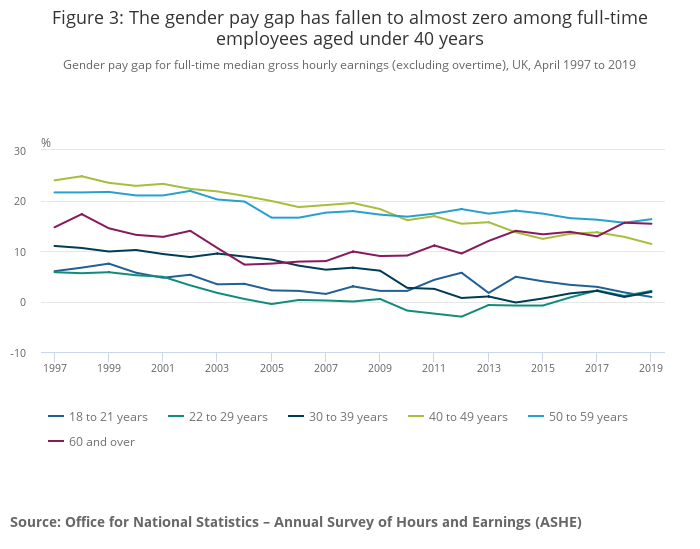

The gap is smaller amongst full time employees at 9%, and almost zero for full time employees under 40. It has fallen faster for younger workers, but remains above 15% for full time workers above 50.

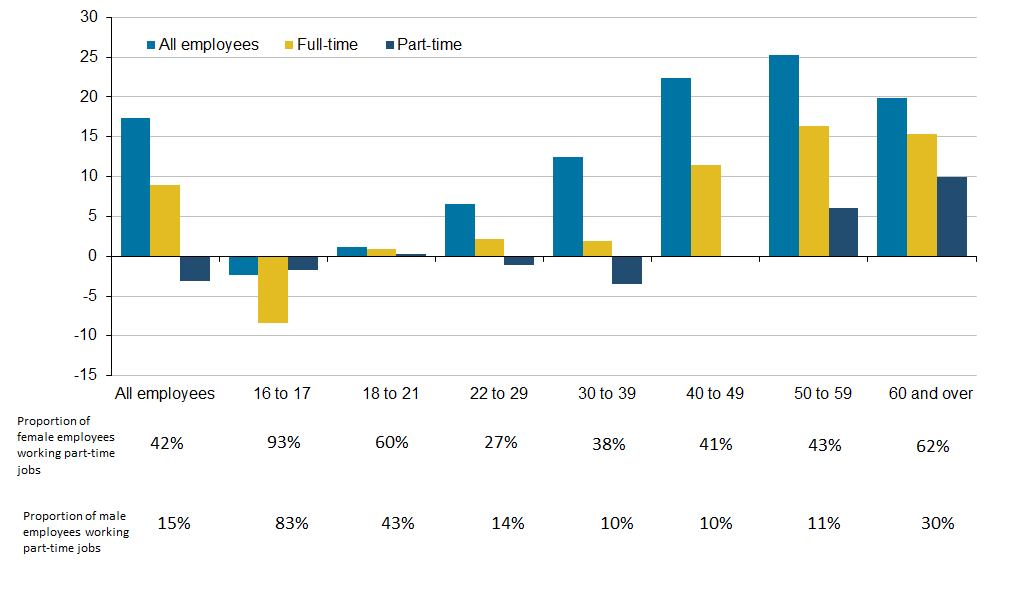

As women get older, and especially after age 30, they increasingly work in part time jobs. Since part time jobs pay less per hour than full time jobs, this affects the wage gap.

Gender pay gap for median gross hourly earnings (excluding overtime) by age group, UK, April 2019

Source: Office for National Statistics – Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE)

Women over 40 are more likely to work in lower paid occupations. Fewer women in their 40s and 50s are managers, directors or senior officials. This is particularly important because pay for those occupations increases by almost 20% between the age bands 30-39 and 40-49. However, this is changing as more women in their 40s are moving into senior executive roles. Between 2011 and 2019, the percentage of female managers, directors and senior officials increased from 27 to 32.4%.

Why care about the pay gap?

The wage gap measures inequality in outcomes, which may be indicating an inequality in opportunity, an unfairness which disproportionately affects women and prevents them earning as much as they otherwise would.

If, on the one hand, the wage gap was reflecting a pure difference in preferences between men and women (e.g. women prefer low paying work) then this would not a problem. For example, poets usually earn much less than advertising copy writers. We do not worry about the poetry-copywriter wage gap, because we presume that the respective creatives freely chose their profession with knowledge of expected wages. It is however important to note that women's preferences for some jobs doesn't rule out the possibility of discrimination affecting the wage gap. Professions where women are concentrated may face indirect discrimination: as "women's work" is seen as less valuable, it may be undervalued and underpaid.

On the other hand, the wage gap might reflect simple prejudice, an unwillingness to pay women as much as men with similar abilities. This is something that policy makers should be really worried about, and try to guard against and rectify. It's important to have a fair labour market both so that women get the jobs and opportunities they deserve, but also so that employers are making the best use of their labour force, and promoting the best, most qualified people.

In order to determine the need for, and the type of, policy response, we need to identify the source of the unequal outcomes. For example, if women are being discriminated against by firms when hiring, then that should be tackled with hiring regulations. If women are leaving firms around childbirth because maternity cover is more generous than paternity cover, then this needs to be addressed. Policymakers need to focus on the cause of inequality.

What causes the pay gap?

The birth of the first child

The gender wage gap starts to widen from the late 20s and early 30s. On average there is a 10% wage gap before the arrival of the first child, but by the time that child is 20, women on average earn 30% less than men.

Women are more likely than men to work part time, or even take time off work, particularly after the birth of a child. They then have less work experience relative to men, and less work experience is associated with lower wages.

Some IFS research has examined the causal pathways involved using some clever econometric techniques.

(They exploit tax and benefit reforms to create a quasi-experiment where women's financial incentives to work and for how many hours are "randomly" affected. This allows them to look at how the differences in work experience between these women then affect later wages.)

According to the IFS research, of the 30% gap between female and male earnings 20 years after the birth of their first child, a quarter already existed prior to the birth of that child. Of the remaining three-quarters, almost half is explained by differences related to time in work.

Most of this effect can be attributed to women working part time, rather than taking time off work altogether. The key mechanism here seems to be the lack of wage progression for part time workers, unlike full time workers. This has the biggest impact on highly educated women (and the wage gap amongst the highly educated), because these women would otherwise have experienced the most wage growth.

But back to our wage gap. The IFS estimates that half of the wage gap between men and women 20 years after the birth of their first child is attributable to the differences in time in work. Which leaves 50% to be explained by other factors.

Bargaining differences

Women are less likely to successfully bargain for higher pay within a given firm. Within firm pay inequality can be partly explained by bargaining behaviour. Card et al (2016) show that women receive only 90% of the pay premiums earned by men, indicating that they are less successful at negotiating higher pay. Whether this is because women don't ask, or simply don't get, is still being debated empirically. While a 2006 paper examining MBA graduates found that women initiate salary negotiations less often than men, a 2018 paper based on a 2014 survey of Australians across occupations found that although women ask as often as men, they only get their desired raise 15% of the time, compared to 20% for men.

Firm choice?

Women tend to work in less productive, lower paying firms. Another great piece of IFS research uses "gross value added per worker" to proxy for productivity, and finds that women are more likely to work at less productive firms than men.

"Average gross value added per worker among the firms that women work for is 22 percent lower than among the firms that men work for." Since more productive firms pay their workers more on average, this suggests that where women and men work is contributing to the pay gap.

Moreover, the gender gap in firm productivity follows the same chronological pattern as the gender wage gap. Women aged 18-34 are 5% less likely than men of the same age to work for the top fifth most productive firms. This increases to 20% by their mid forties. This pattern is mirrored in the gender commuting gap, whereby the time spent commuting by women falls after the birth of the first child, unlike that of men. It is possible that these three patterns are related: if women are bearing more of the childcare burden, then they may be constrained in their choice of employer by a need to work close to home, thus reducing their options and reducing their wages.

So, what can we conclude?

The data I have looked at in this post implies that women are losing out on salary (and career) progression due to moving into part-time work. Policies valuing, integrating and improving progression pathways for non-traditional work, including part time work, self-employment and gig economy jobs, might benefit women and reduce the gender pay gap. Improving labour market flexibility in this way will also allow the UK to make the best use of its whole labour force, rather than artificially constraining itself to just traditional full-time workers.

Bargaining asymmetries could be addressed with laws requiring salary transparency, e.g. for average pay across a grade. This would allow workers to know if they are being underpaid, and give them valuable information to improve bargaining power.

Finally, the gender productivity and commuting gaps imply that women may be taking on a greater share of childcare responsibilities than fathers, leading them to constrain their choice of employer more than men. If this is by choice, then it leaves no policy implications. Otherwise, the source of asymmetrical decision making should be addressed.

If you enjoyed the read...

Then why not sign up to my mailing list to get notified when I post anything new?